I’ve heard a lot of praise for the apprenticeship model of learning in the software world over the past couple of years and with the help of some recently published research I’d like to say,

“you’re doing it wrong.”

I just read a fascinating paper in the Anthropology of Work Review (v.33 n.2) by Dr. David F. Lancy. In it, he summarizes observations from the ethnographic record (citing about 70 sources) in an attempt to describe the nature of apprenticeship as a training model with examples from the ancient Sumerians to the present. I would expect that when trying to establish the borders of a broad concept with that much data, each data set would serve to narrow the definition by producing more deviations reducing the size of the common set. Imagine my surprise to learn that Lancy had the opposite experience, ultimately arriving at eleven common traits of apprenticeships that span time and space.

I just read a fascinating paper in the Anthropology of Work Review (v.33 n.2) by Dr. David F. Lancy. In it, he summarizes observations from the ethnographic record (citing about 70 sources) in an attempt to describe the nature of apprenticeship as a training model with examples from the ancient Sumerians to the present. I would expect that when trying to establish the borders of a broad concept with that much data, each data set would serve to narrow the definition by producing more deviations reducing the size of the common set. Imagine my surprise to learn that Lancy had the opposite experience, ultimately arriving at eleven common traits of apprenticeships that span time and space.

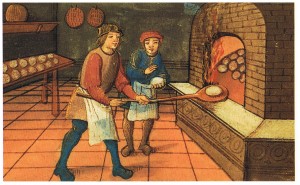

But first, what is apprenticeship? If the goal is to pass along knowledge or skills, then public workshops would be more efficient. Lancy observes that an important feature of apprenticeship is control over fungible skills and maintenance of the social status of masters. An is a threat to the master’s reputation during training and to the master’s income after training, so the master has every incentive to maintain a high degree of control over the pupil during and after the apprenticeship period.

So these are the eleven common elements of apprenticeship that Lancy discovered.

Access is exclusive – it’s very difficult to obtain an apprenticeship position, with access limited by wealth, position, caste, or talent.

The apprentice moves into the master’s sphere of influence – Especially in the case of juvenile apprenticeships, the apprentice lives with the master and is fully under his discipline and control, forfeiting the nurturing networks previously enjoyed.

The relationship between master and apprentice is highly hierarchical.

Apprentices begin by performing menial labor often unrelated to the skill to be learned. The function of this period is to establish the hierarchy, weed out the undisciplined and unmotivated, and to socialize the apprentice to the domain.

When the apprentice does begin to learn, tasks are laddered in a gradual progression of complexity.

There is very little of what we’d call “teaching” involved. Most learning involves watching and copying the master. Questions are not tolerated as they undermine the master’s role. Most feedback is negative.

Physical and emotional abuse are very common. The reasons are mixed. There may be some benefit to the apprentice to go through a trial by fire, as it were, but the most compelling explanation for abuse is that masters benefit from the years of service that apprentices give but see their graduation as a threat, so the most useful apprentices serve the master for years and then quit or run away. Recently on a thread I started on Twitter, some programmers have shared horror stories of workplace violence in dev teams. I wonder if there’s a connection?

Creativity is discouraged strongly. Apprentices learn to copy, usually only the simpler work of the master, never to express originality.

The master often keeps some of their techniques or knowledge to himself to avoid creating too perfect a competitor.

Apprenticeship is a very lengthy process and rarely successful (for the apprentice). The master may get years of free or cheap labor before the apprentice fails or leaves.

Some ceremony marks the completion of the apprenticeship period.

I am not suggesting that we’d do a better job training novice programmers if we beat them more often, or forced them to live in the office (although that seems to work for Google). What I find exciting about this literature survey is that it implies that this thing we call apprenticeship in the software world is not apprenticeship at all. It’s something else, perhaps something new, that has emerged in our discipline. That means that we are not tied to our notions of what apprenticeship is or should be and we are free to embrace our discovery and experiment with it, creating as we go a new and more powerful method of raising a new generation of programmers.